I'll be honest: I didn't consciously think about my work habits until last year. I just…worked. But when I started aggressively treating my anxiety last year, it turned out that my anxiety disorder masked ADHD symptoms—and powered my productivity at work.

Thanks to treatment, my brain actively rejected the anxiety-related habits I honed over the years (cool) and forgot how to be productive (not so cool). Much like relearning to walk after an injury, I had to relearn effective work habits from scratch.

To do that, I conducted what I dubbed "productivity experiments" to figure out my new work habits. If you have unproductive work habits—or want to adopt better ones—here's how to run your own experiments.

The benefits of productivity experiments

The world of personal productivity is filled with unnecessary shame. If you're unproductive, it's often considered a moral failing. News flash: you can be productive and a terrible person. And shame is a terrible motivator for building habits that stick.

That's why I approached my habit-rebuilding like a scientific experiment and why it worked.

You can test one thing at a time. In science, experiments need at least one control—something that won't change throughout the trial—so you can accurately measure and determine the results. So you don't have to try all the productivity hacks out there. Just try one thing and see what happens.

It takes the sting out of failure. In experiments, failure isn't associated with self-value or worth. Failure is just a result used to refine the hypothesis and test again. If you try a tactic that doesn't work for you, it's just a data point, not a measure of your ability.

You'll learn what works best for you—and what doesn't. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of experiments back new scientific discoveries. Similarly, each experiment will lead you closer to a solution that works for you, which might be different from what you started with. You'll also spot trends with the failures, which will help you rule out methods faster.

The experimental approach wasn't an excuse for me to roleplay as an evil scientist (though it didn't hurt either). Ultimately, it helped me be kinder to myself as I tried to figure out the habits worth adopting.

How to run your own productivity experiment

The keyword in personal productivity is personal. What works for one person may not work for you. This approach isn't prescriptive but will help you learn what works for you.

How to run a productivity experiment:

Start with the problem, not the solution

When we're trying to change a habit—whether at work or at home—we tend to get it backward and focus on the solution first. (If it's in a book, it must be good, right?) But if you're not crystal clear on the problem you're trying to solve, you might be wasting your energy on changing the wrong thing.

Instead, start with the issue you're facing. I'm a big fan of "issue logs," where you can track problems as they arise without judgment. This will be the main point your productivity experiment will try to answer or solve.

Your issue log can take whatever form works for you, but it should include the following:

The issue you're facing. The issue should affect your ability to show up as you'd like or what you know you're capable of. Be careful not to list the things you "should" do because of some ideal standard. For example, "I struggle to journal at the end of every day" can be an issue if you notice that journaling improves your focus, but it's not an issue because you feel it's the so-called "ideal" thing to do.

Why it's an issue. What happens when this issue persists? Building off the earlier example, maybe the inability to relax at the end of the workday makes it hard for you to show up at home or makes you feel tired all the time.

Why solving the issue matters to you. What will you be able to accomplish if you adopt a habit to offset this issue? What would be the ideal outcome for you?

Do you have a solution in mind? This can be a simple yes or no answer. Sometimes we know what the solution is but don't get to it because of other demands on our time. Don't worry if you don't have a solution yet. We'll cover that in the next section.

Don't feel compelled to tackle each issue immediately after you record it. I recommend keeping a running log for a week or so. If it's genuinely an issue, it will keep coming up.

Choose your focus

If you've kept a running issue log, you'll have a healthy list of issues. Scientific experiments test one hypothesis at a time. Similarly, you'll pick one issue to focus your productivity experiment on.

Here are a few ways to prioritize:

The most immediate issue. This could be a time-sensitive issue, such as finding a better way to prep for meetings or solving a focus issue before a big project starts.

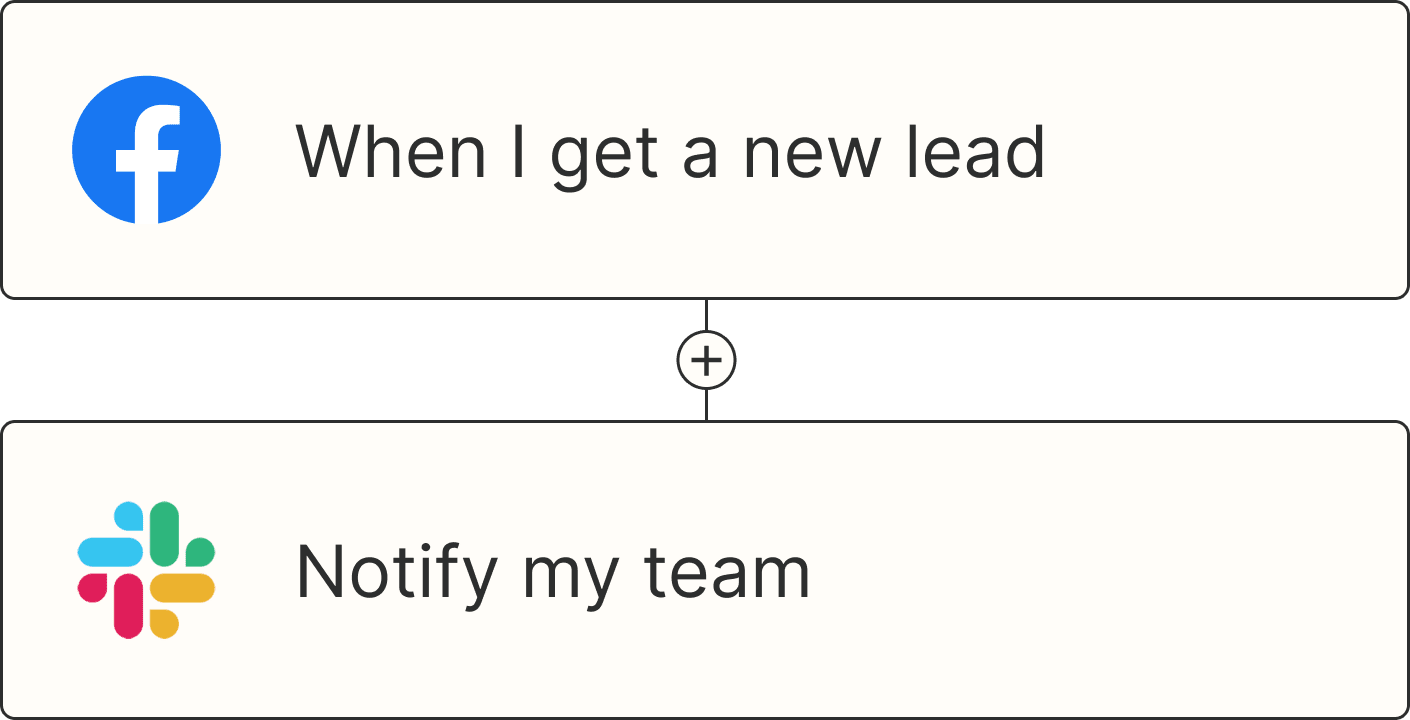

The quick win. I love quick wins because they can build momentum. For example, I identified "too much time on Slack" as an issue. I knew it would be a quick win because I could limit my Slack time to recurring calendar events or use a distraction blocker.

The issue that trips you up. This could be an issue that has a domino effect on the rest of your day, impacts your team, or makes you rage over how bothersome it is.

What you decide to focus on first is up to you. Some people like to start with the most challenging task first, but if a quick win is more your style, that's ok too.

Select a tactic to test

You've identified the issue that you'll focus on for your experiment. Now comes the fun part: picking the method or tactic you'll try to adopt as a habit.

Your issue focus will likely determine the kinds of methods you try, and you might have a few ideas in mind already. If not, research and find a few tactics that pique your interest. (The Zapier blog you're reading is an excellent place to start.)

There are only two rules for this stage:

Avoid getting too invested in a particular approach. You don't want to be crushed if a method you pinned all your hopes on doesn't work out. Remember, failure is just a data point you can use to refine your experiment.

Pick one method to try. Avoid the temptation to try all the things. Remember, experiments need at least one thing that doesn't change so you can accurately evaluate your experiment. And don't worry; we'll introduce variety later on.

Run your experiment

Now it's time to run your experiment. Set up whatever you need, and try the method for a week. Pay attention to what works and what doesn't.

Here are a few things to watch for:

How do you feel? Is it addressing the issue you're trying to solve? If not, why?

Is the method too cumbersome or incompatible with your lifestyle for it to become a habit?

Does this tactic show promise but needs tweaking to work for you?

Write down your observations. The habit may fall into one of three categories:

Promising: This is the "green light" to continue this habit.

Needs adjustment: This habit could work, but it needs tweaking to work for you. If this were a traffic light, this would be the yellow signal to slow down. Make a note of any adjustments you can make.

Not working: This habit doesn't work for you, period. This is a red light or stop sign.

Now what? If a habit is in the "promising" category, continue. Once you feel comfortable maintaining this habit without much thought, return to your issue log and run another productivity experiment.

If a habit needs an adjustment, tweak it according to your observations, and repeat the experiment until it gets a green light. If you can tweak the habit until it's obvious, easy, attractive, and satisfying to complete, you're more likely to keep at it.

And if a habit isn't working? Drop it, and try another tactic. It's better to build upon something that's likely to succeed instead of wasting your time on a habit you'll never stick to.

For example, I needed a better way to manage my time throughout the day and pace myself, so I didn't end the day burned out. A productivity experiment quickly taught me that time-tracking apps—especially ones that require me to start a timer—aren't effective because it doesn't help me manage time at the moment. What worked? Pomodoro timers.

Experiment and find what sticks

It takes time for any habit to stick, but with an experimental approach, you'll quickly weed out counterproductive habits to find the ones that work for you.

Need some more experimentation inspiration? Here are a few to get you started.