I'm a preschool teacher, a social sciences researcher, and a bit of a Luddite. My Facebook page is unchanged from its initial setup back when it was still The Facebook, and I use Snapchat exclusively with my wife for sharing pictures of my kids and dog. (Mostly the dog.) So you might think that, when it comes to automation, I'd be scared of future fleets of Rosey the Robots taking over my childcare duties.

Because letting computers handle things takes the humanity out of it all, right?

Not at all. In fact, trying to complete tasks as efficiently as possible is one of the most human things we do. A shift from effortful completion of tasks to more automatic processing is at the core of many theories of human development. And some theories see that shift as the essential mechanism for growth and development.

Whether it's basic curricular goals in school or cultural knowledge passed down over generations, this efficiency—or automaticity, in education-speak—is the basis of learning.

How we grow

Back in the '70s and '80s, scholars started using language that sounds vaguely computer-y to explain children's development. Specifically, the Neo-Piagetian movement focused on the brain's power to process and retain information, or what scholar Juan Pascual-Leone called information processing capacity (IPC).

In short, an individual's ability to complete a task depends on their ability to

hold relevant information in their mind and

process the necessary steps to complete it.

But practice with a task makes it easier: the new becomes familiar, the familiar becomes habitual, and the brain regains space for bigger and better things.

So learning, according to the theory, is the process of developing automaticity: the ability to perform tasks with little effort, planning, or processing.

Researcher Robbie Case took this a step further. He said that improvements in IPC explain all of human cognitive development from infancy to adulthood—from learning to walk to solving complex logic problems. As individuals get better at tasks and the effort needed for those tasks goes down, the brain can learn to combine multiple tasks into a single, fluid "consolidation." For example: as a newborn, the ability to squeeze your hand combines with the ability to stretch your arm, and suddenly you can grasp a toy at arm's length. Two skills become one, and you've moved up a level. Congrats, tiny human!

These consolidations make every move—be it physical, mental, social, or emotional—more efficient in terms of the effort it takes to perform. They also become skills in their own right that can be consolidated further with others, laying the groundwork for a snowball of overall development.

Automaticity and the brain

As automaticity develops, your brain starts to work differently.

A 2012 study demonstrated that brain scans of people performing a novel task showed activity mostly in the prefrontal cortex, which is used in conscious planning, organizing, and focusing, among other difficult cognitive skills. But as people did the same task over and over, brain activity moved to a more internal part of the brain that uses less conscious effort.

Imagine how natural it feels to do something simple like switch on the windshield wipers in your car. But when you hop into a rental car, you have to think for a second to make it work. Which switch is it again? Do you twist it or push it?

Switching cars is much like switching tasks: you're completely physically capable of doing it (it's not like learning a new sport), but the automatic process just isn't in your head yet. After doing it many many times, the task will be easier and more automatic because the way your brain receives and performs its demands will have changed.

Our own neural networks reprogram themselves to behave as efficiently as possible.

If you're not sure when to automate a task, start here. Then take a look at these 5 things you should automate today.

How automaticity helps in school

This is true for physical tasks, but also complex mental ones like reading. In fact, one of the key early indicators of literacy is how efficiently a child can name a series of letters, or rapid automatized naming (RAN).

In general, the more automatically a child processes letters at age 5 or 6, the better they will read later on. Before you think this is the magic bullet for literacy and go out training young children to recite the ABCs in timed competitions, evidence suggests that training for RAN doesn't improve reading. It's not about training—it's that the child's brain is already going through the "programming" needed to read well. Neuroscientists have found that developing literacy actually changes the way a person's brain is structured.

Automaticity is about connecting the areas of the brain used for reading: the visual and the linguistic. If you've ever watched a 5-year-old read out loud, you know early readers use a ton of brainpower to decode those marks on a page into words they know.

Building pathways in the brain that allow for automaticity frees a child to use their processing power for things like comprehension and interpretation. Automating the process gets them to the good stuff.

How we develop expertise

The value of automaticity has found its place in popular science in recent years, too.

In his 2008 book Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell popularized the so-called 10,000 hours rule. He said it takes, on average, 10,000 hours of deliberate practice to achieve expertise in a field.

He, of course, was writing about things like musicianship or neurosurgery, but the basic mechanism applies to everyday tasks as well (luckily with considerably less time). Essentially, practice helps us learn to perform fundamental tasks without thinking. This may not be great when you slip into autopilot while driving home from work, but it's incredibly helpful when you engage in complex tasks that don't involve heavy machinery.

Lots of commentary has gone into debunking the 10,000 hours rule, demonstrating how actual elite performance depends on more than just practice time—there's quality of practice time, aptitude, and stylistic elements. (Gladwell himself has acknowledged as much.) For example, there is little technical variation among a large group of expert violinists who all put in loads of human hours to perfect their craft. But their natural ability, style, and other factors separate the top one percent from the rest.

In other words, 10,000 hours of practice got everyone to automaticity: the same technical and physical competency of playing the violin. And that freed up space for the extra something to shine through—or not shine through, as the case may be.

Automation is not anti-human

Legendary basketball coach John Wooden also understood the importance of automaticity. When talking about doing drills, he framed it for his players as doing things over and over in order to achieve automaticity, so they could perform the fundamentals without even thinking about it.

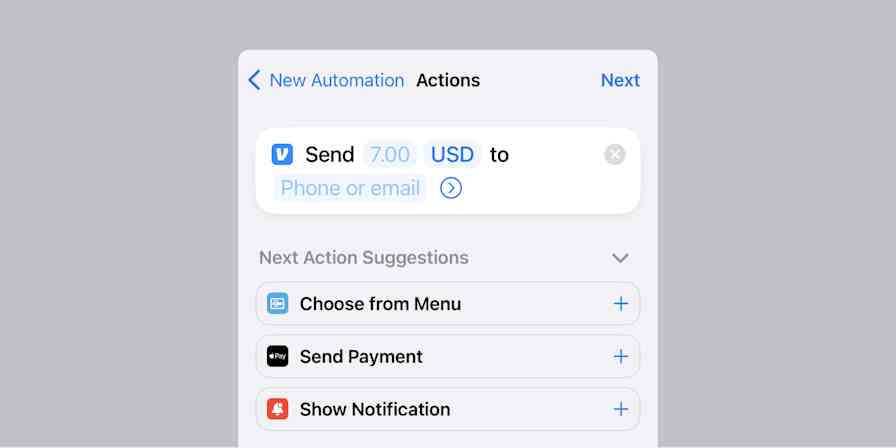

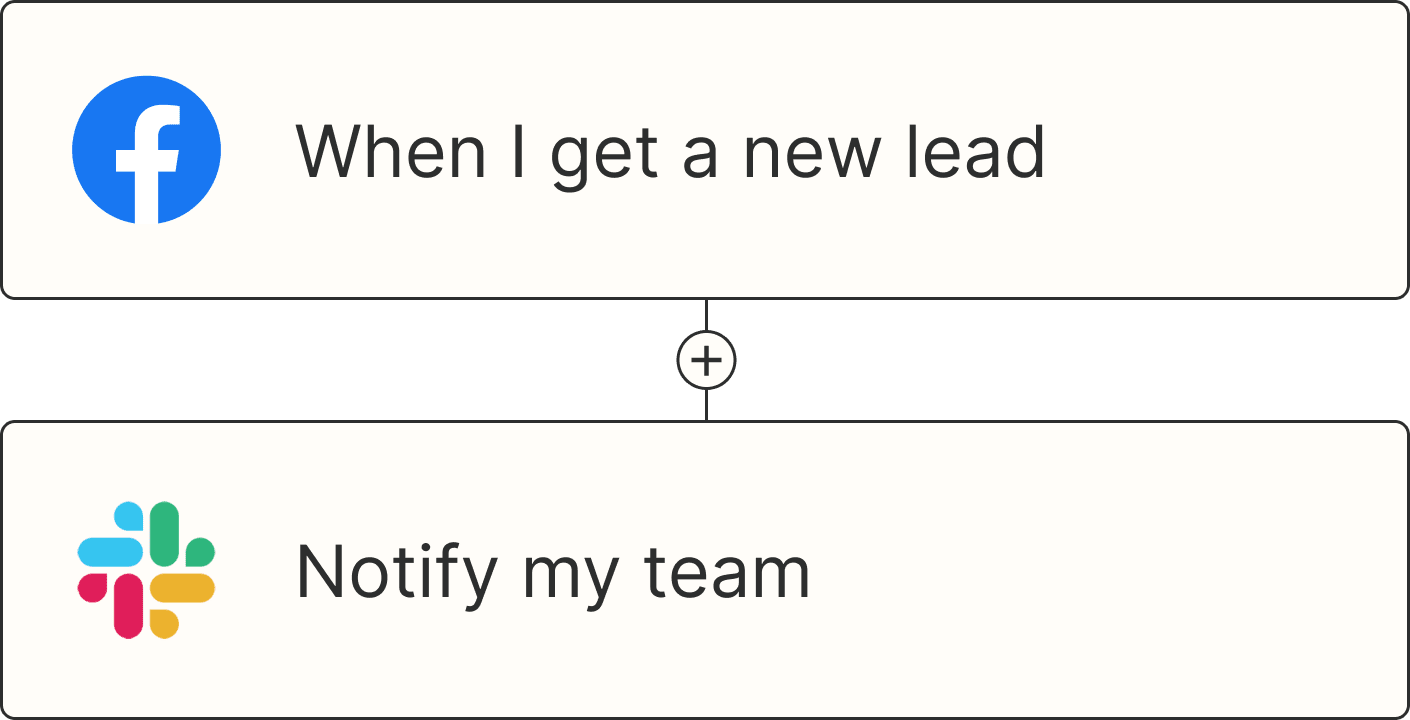

Practicing free throws is one thing, but who really wants to repeat mundane tasks like canned email responses or migrating data from Excel to Airtable until it becomes second nature?

That's where tools come in.

Automating tasks using physical or digital tools offers the promise to free up cognitive processing space in much the same way internal automaticity does. It allows tasks to be performed quickly and reliably without much effort from an individual person. Instead, that person can do the "higher-order" work a tool can't yet handle.

In that way, automation is kind of like the externalization of automaticity. It's another effort to satisfy something that's innately human: the need to complete tasks efficiently.

How we progress

I'm certainly not advocating for full-on automation of everything. But developing tools, systems, and processes to increase efficiency is also a fundamentally human endeavor.

Written language itself is a tool invented thousands of years ago to carry knowledge that previously had to be memorized and handed down orally. Ancient Greeks thought of this oral tradition as one of the great virtues, and Socrates was famously opposed to literacy—he thought it would make it too easy for people to access information. There probably aren't many people now who think things would be better if Socrates had his way.

The benefits of these tools, systems, and processes go beyond the space that they're designed to disrupt. They build on each other like a kind of evolutionary adaptation. We develop tools to lighten the workload, physical or cognitive. In doing so, we free up space not only for ourselves, but for generations to come. Then those generations get to start from a baseline of efficiency that we had to work for—and the cycle continues.

I can't count the number of times my fellow preschool teachers and I longed for a tool that could effectively and efficiently document a wonderful moment in a child's day. Doing so would both free us up to do what we do best—interact with children—and provide better, more individualized information for assessing a child's growth. This tool could consolidate procedures and make space for humanity to shine.

The list of tools I've tried is by no means exhaustive, but so far they've all felt clunky in one way or another. But that just means I get to imagine that one of the children I've taught will put their skills together, become an expert, and make a better tool.